Classical Chinese on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

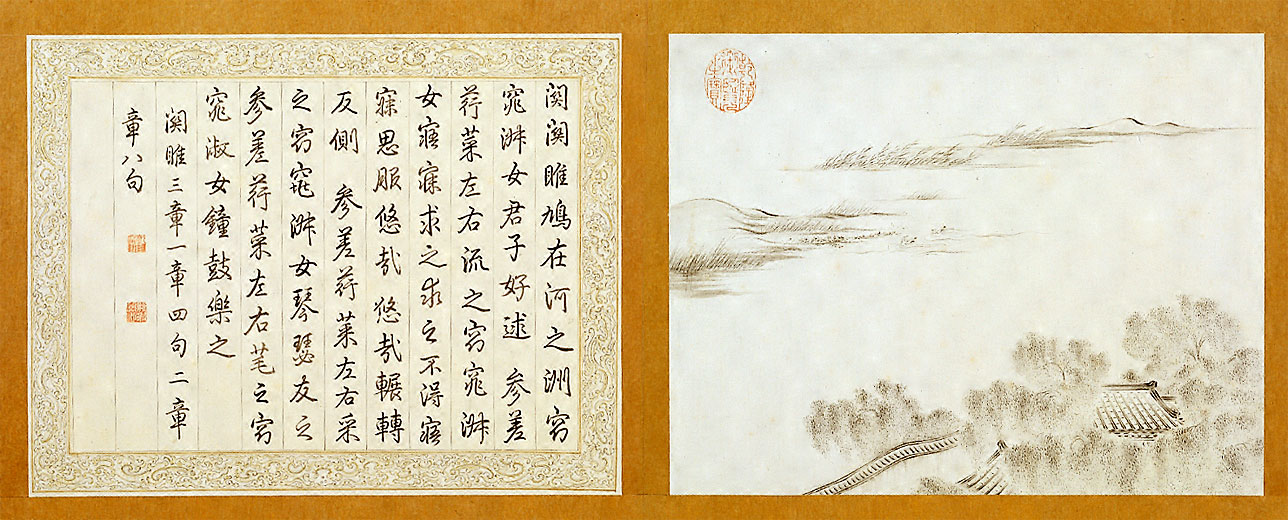

Classical Chinese, also known as Literary Chinese (古文 ''gǔwén'' "ancient text", or 文言 ''wényán'' "text speak", meaning

"literary language/speech"; modern vernacular: 文言文 ''wényánwén'' "text speak text", meaning

"literary language writing"), is the language of the classic literature from the end of the  Literary Chinese is known as ' (, " Han writing") in Japanese, ' in Korean (but see also ') and ' () or ''Hán văn'' () in Vietnamese.

Literary Chinese is known as ' (, " Han writing") in Japanese, ' in Korean (but see also ') and ' () or ''Hán văn'' () in Vietnamese.

Classical Chinese was the main form used in Chinese literary works until the May Fourth Movement (1919), and was also used extensively in Japan, Korea, and Vietnam. Classical Chinese was used to write the Hunmin Jeongeum proclamation in which the modern Korean alphabet (

Classical Chinese was the main form used in Chinese literary works until the May Fourth Movement (1919), and was also used extensively in Japan, Korea, and Vietnam. Classical Chinese was used to write the Hunmin Jeongeum proclamation in which the modern Korean alphabet (

Classical Chinese for Everyone

Bryan Van Norden, 2004

Alex Amies, 2013

Chinese Texts: A Classical Chinese course

Mark Edward Lewis, 2014

Literary Chinese

Robert Eno, 2012-2013 (to access the book use provided PDF index file)

A Primer in Chinese Buddhist Writings

John Kieschnick, 2015

John Cikoski, 2011.

Microsoft Translator releases literary Chinese translation

(''Microsoft Translator Blog,'' August 25, 2021) {{Authority control Chinese language Chinese Korean language Japanese language Vietnamese writing systems

Spring and Autumn period

The Spring and Autumn period was a period in Chinese history from approximately 770 to 476 BC (or according to some authorities until 403 BC) which corresponds roughly to the first half of the Eastern Zhou period. The period's name derives fr ...

through to the either the start of the Qin dynasty or the end of the Han dynasty, a written form of Old Chinese (上古漢語, ''Shànɡɡǔ Hànyǔ''). Classical Chinese is a traditional style of written Chinese that evolved from the classical language, making it different from any modern spoken form of Chinese. Literary Chinese was used for almost all formal writing in China

China, officially the People's Republic of China (PRC), is a country in East Asia. It is the world's most populous country, with a population exceeding 1.4 billion, slightly ahead of India. China spans the equivalent of five time zones and ...

until the early 20th century, and also, during various periods, in Japan

Japan ( ja, 日本, or , and formally , ''Nihonkoku'') is an island country in East Asia. It is situated in the northwest Pacific Ocean, and is bordered on the west by the Sea of Japan, while extending from the Sea of Okhotsk in the north ...

, Ryukyu, Korea and Vietnam. Among Chinese speakers, Literary Chinese has been largely replaced by written vernacular Chinese, a style of writing that is similar to modern spoken Mandarin Chinese, while speakers of non-Chinese languages have largely abandoned Literary Chinese in favor of their respective local vernaculars. Although languages have evolved in unique, different directions from the base of Literary Chinese, many cognates can be still found between these languages that have historically written in Classical Chinese.

Literary Chinese is known as ' (, " Han writing") in Japanese, ' in Korean (but see also ') and ' () or ''Hán văn'' () in Vietnamese.

Literary Chinese is known as ' (, " Han writing") in Japanese, ' in Korean (but see also ') and ' () or ''Hán văn'' () in Vietnamese.

Definitions

Classical Chinese refers to the written language of the classical period of Chinese literature, from the end of theSpring and Autumn period

The Spring and Autumn period was a period in Chinese history from approximately 770 to 476 BC (or according to some authorities until 403 BC) which corresponds roughly to the first half of the Eastern Zhou period. The period's name derives fr ...

(early 5th century BC) to the end of the Han dynasty (AD 220), while Literary Chinese is the form of written Chinese used from the end of the Han dynasty to the early 20th century, when it was replaced by vernacular written Chinese. There is also a stricter definition for the Classical period, ranging from Confucius (551–479 BCE) to the foundation of the Qin dynasty.

Literary Chinese is often also referred to as "Classical Chinese", but sinologists generally distinguish it from the language of the early period. During this period, the dialects of China became more and more disparate and thus the Classical written language became less and less representative of the varieties of Chinese (cf. Classical Latin, which was contemporary to the Han Dynasty, and the Romance languages of Europe). Although authors sought to write in the style of the Classics, the similarity decreased over the centuries due to their imperfect understanding of the older language, the influence of their own speech, and the addition of new words.

This situation, the use of Literary Chinese throughout the Chinese cultural sphere despite the existence of disparate regional vernaculars, is called diglossia. It can be compared to the position of Classical Arabic

Classical Arabic ( ar, links=no, ٱلْعَرَبِيَّةُ ٱلْفُصْحَىٰ, al-ʿarabīyah al-fuṣḥā) or Quranic Arabic is the standardized literary form of Arabic used from the 7th century and throughout the Middle Ages, most notab ...

relative to the various regional vernaculars in Arab lands, or of Latin in medieval Europe. The Romance languages continued to evolve, influencing Latin texts of the same period, so that by the Middle Ages, Medieval Latin included many usages that would have been foreign to the Romans. The coexistence of Classical Chinese and the native languages of Japan, Korea and Vietnam can be compared to the use of Classical Latin in nations that natively speak non-Latin-derived Germanic languages or Slavic languages, to the position of Arabic in Persia, or the position of the Indic language Sanskrit in South India and Southeast Asia. However, the non-phonetic Chinese writing system causes a unique situation where the modern pronunciation of the classical language is far more divergent (and heterogeneous, depending on the native – not necessarily Chinese – tongue of the reader) than in analogous cases, complicating understanding and study of Classical Chinese further compared to other classical languages.

Christian missionaries coined the term Wen-li () ("the principles of literature", "the book language as opposed to the colloquial") for Literary Chinese. Though composed from Chinese roots, this term was never used in that sense in Chinese, and was rejected by non-missionary sinologues.

Pronunciation

Chinese characters are not alphabetic and only rarely reflectsound changes

A sound change, in historical linguistics, is a change in the pronunciation of a language. A sound change can involve the replacement of one speech sound (or, more generally, one phonetic feature value) by a different one (called phonetic chang ...

. The tentative reconstruction of Old Chinese is an endeavor only a few centuries old. As a result, Classical Chinese is not read with a reconstruction of Old Chinese pronunciation; instead, it is always read with the pronunciations of characters categorized and listed in the Phonology Dictionary (韻書; pinyin: ''yùnshū'', " rhyme book") officially published by the Governments, originally based upon the Middle Chinese pronunciation of Luoyang in the 2nd to 4th centuries. With the progress of time, every dynasty has updated and modified the official Phonology Dictionary. By the time of the Yuan Dynasty and Ming Dynasty, the Phonology Dictionary was based on early Mandarin. But since the Imperial Examination required the composition of Shi genre, in non-Mandarin speaking parts of China such as Zhejiang, Guangdong and Fujian, pronunciation is either based on everyday speech as in Cantonese; or, in some varieties of Chinese (e.g. Southern Min

Southern Min (), Minnan (Mandarin pronunciation: ) or Banlam (), is a group of linguistically similar and historically related Sinitic languages that form a branch of Min Chinese spoken in Fujian (especially the Minnan region), most of Taiwan ( ...

), with a special set of pronunciations used for Classical Chinese or "formal" vocabulary and usage borrowed from Classical Chinese usage. In practice, all varieties of Chinese combine these two extremes. Mandarin and Cantonese, for example, also have words that are pronounced one way in colloquial usage and another way when used in Classical Chinese or in specialized terms coming from Classical Chinese, though the system is not as extensive as that of Southern Min or Wu. (See Literary and colloquial readings of Chinese characters)

Japanese, Korean or Vietnamese readers of Classical Chinese use systems of pronunciation specific to their own languages. For example, Japanese speakers use ''On'yomi'' pronunciation when reading the kanji of words of Chinese origin such as 銀行 (''ginkō'') or the name for the city of ''Tōkyō'' (東京), but use ''Kun'yomi'' when the kanji represents a native word such as the reading of 行 in 行く (''iku'') or the reading of both characters in the name for the city of ''Ōsaka'' (大阪), and a system that aids Japanese speakers with Classical Chinese word order.

Since the pronunciation of all modern varieties of Chinese is different from Old Chinese or other forms of historical Chinese (such as Middle Chinese), characters that once rhyme

A rhyme is a repetition of similar sounds (usually, the exact same phonemes) in the final stressed syllables and any following syllables of two or more words. Most often, this kind of perfect rhyming is consciously used for a musical or aesthetic ...

d in poetry may not rhyme any longer, or vice versa. Poetry and other rhyme-based writing thus becomes less coherent than the original reading must have been. However, some modern Chinese varieties

Chinese, also known as Sinitic, is a branch of the Sino-Tibetan language family consisting of hundreds of local varieties, many of which are not mutually intelligible. Variation is particularly strong in the more mountainous southeast of main ...

have certain phonological characteristics that are closer to the older pronunciations than others, as shown by the preservation of certain rhyme structures.

Another phenomenon that is common in reading Classical Chinese is homophony (words that sound the same). More than 2,500 years of sound change separates Classical Chinese from any modern variety, so when reading Classical Chinese in any modern variety of Chinese (especially Mandarin) or in Japanese, Korean, or Vietnamese, many characters which originally had different pronunciations have become homonyms. There is a famous Classical Chinese poem written in the early 20th century by the linguist Chao Yuen Ren

Yuen Ren Chao (; 3 November 1892 – 25 February 1982), also known as Zhao Yuanren, was a Chinese-American linguist, educator, scholar, poet, and composer, who contributed to the modern study of Chinese phonology and grammar. Chao was born an ...

called the '' Lion-Eating Poet in the Stone Den'', which contains only words that are now pronounced with various tones in Mandarin

Mandarin or The Mandarin may refer to:

Language

* Mandarin Chinese, branch of Chinese originally spoken in northern parts of the country

** Standard Chinese or Modern Standard Mandarin, the official language of China

** Taiwanese Mandarin, Stand ...

. It was written to show how Classical Chinese has become an impractical language for speakers of modern Chinese because Classical Chinese when spoken aloud is largely incomprehensible. However the poem is perfectly comprehensible when read silently because Literary Chinese, by its very nature as a ''written'' language using a logographic writing system, can often get away with using homophones that even in spoken Old Chinese would not have been distinguishable in any way.

The situation is analogous to that of some English words that are spelled differently but sound the same, such as "meet" and "meat", which were pronounced and respectively during the time of Chaucer, as shown by their spelling. However, such homophones are far more common in Literary Chinese than in English. For example, the following distinct Old Chinese words are now all pronounced ''yì'' in Mandarin: ''*ŋjajs'' 議 "discuss", ''*ŋjət'' 仡 "powerful", ''*ʔjup'' 邑 "city", ''*ʔjək'' 億 "100,000,000", ''*ʔjəks'' 意 "thought", ''*ʔjek'' 益 "increase", ''*ʔjik'' 抑 "press down", ''*jak'' 弈 "Chinese chess", 逸 "flee", 翼 "wing", 易 "change", 易 "easy", and 蜴 "lizard".

Romanizations have been devised giving distinct spellings for the words of Classical Chinese, together with rules for pronunciation in various modern varieties.

The earliest was the Romanisation Interdialectique (1931–2) of French missionaries Henri Lamasse

Henri is an Estonian, Finnish, French, German and Luxembourgish form of the masculine given name Henry.

People with this given name

; French noblemen

:'' See the 'List of rulers named Henry' for Kings of France named Henri.''

* Henri I de Montm ...

, of the Paris Foreign Missions Society, and Ernest Jasmin, based on Middle Chinese, followed by linguist Wang Li's ''wényán luómǎzì'' (1940) based on Old Chinese, and Chao's General Chinese Romanization (1975).

However none of these systems has seen extensive use.

Grammar and lexicon

Classical Chinese is distinguished from written vernacular Chinese in its style, which appears extremely concise and compact to modern Chinese speakers, and to some extent in the use of differentlexical items

In lexicography, a lexical item is a single word, a part of a word, or a chain of words (catena) that forms the basic elements of a language's lexicon (≈ vocabulary). Examples are ''cat'', ''traffic light'', ''take care of'', ''by the way'' ...

(vocabulary). An essay in Classical Chinese, for example, might use half as many Chinese characters as in vernacular Chinese to relate the same content.

In terms of conciseness and compactness, Classical Chinese rarely uses words composed of two Chinese characters; nearly all words are of one syllable

A syllable is a unit of organization for a sequence of speech sounds typically made up of a syllable nucleus (most often a vowel) with optional initial and final margins (typically, consonants). Syllables are often considered the phonological "bu ...

only. This stands directly in contrast with modern Northern Chinese varieties including Mandarin, in which two-syllable, three-syllable, and four-syllable words are extremely common, whilst although two-syllable words are also quite common within modern Southern Chinese varieties, they are still more archaic in that they use more one-syllable words than Northern Chinese varieties. This phenomenon exists, in part, because polysyllabic words evolved in Chinese to disambiguate homophones that result from sound changes. This is similar to such phenomena in English as the ''pen–pin'' merger of many dialects in the American south and the ''caught-cot'' merger of most dialects of American English: because the words "pin" and "pen", as well as "caught" and "cot", sound alike in such dialects of English, a certain degree of confusion can occur unless one adds qualifiers like "ink pen" and "stick pin." Similarly, Chinese has acquired many polysyllabic words in order to disambiguate monosyllabic words that sounded different in earlier forms of Chinese but identical in one region or another during later periods. Because Classical Chinese is based on the literary examples of ancient Chinese literature, it has almost none of the two-syllable words present in modern Chinese varieties.

Classical Chinese has more pronoun

In linguistics and grammar, a pronoun ( abbreviated ) is a word or a group of words that one may substitute for a noun or noun phrase.

Pronouns have traditionally been regarded as one of the parts of speech, but some modern theorists would n ...

s compared to the modern vernacular. In particular, whereas Mandarin has one general character to refer to the first-person pronoun ("I"/"me"), Literary Chinese has several, many of which are used as part of honorific

An honorific is a title that conveys esteem, courtesy, or respect for position or rank when used in addressing or referring to a person. Sometimes, the term "honorific" is used in a more specific sense to refer to an honorary academic title. It ...

language (see Chinese honorifics).

In syntax

In linguistics, syntax () is the study of how words and morphemes combine to form larger units such as phrases and sentences. Central concerns of syntax include word order, grammatical relations, hierarchical sentence structure ( constituency) ...

, Classical Chinese is always ready to drop subjects and objects when a reference to them is understood ( pragmatically inferable). Also, words are not restrictively categorized into parts of speech: nouns are commonly used as verbs, adjectives as nouns, and so on. There is no copula in Classical Chinese, "是" ( pinyin: ''shì'') is a copula in modern Chinese but in old Chinese it was originally a near demonstrative

Demonstratives (abbreviated ) are words, such as ''this'' and ''that'', used to indicate which entities are being referred to and to distinguish those entities from others. They are typically deictic; their meaning depending on a particular frame ...

("this"); the modern Chinese for "this" is "這" ( pinyin: ''zhè'').

Beyond grammar and vocabulary differences, Classical Chinese can be distinguished by literary and cultural differences: an effort to maintain parallelism and rhythm, even in prose works, and extensive use of literary and cultural allusions, thereby also contributing to brevity.

Many final particles (歇語字, ''xiēyǔzì'') and interrogative particles are found in Literary Chinese.

Historical use

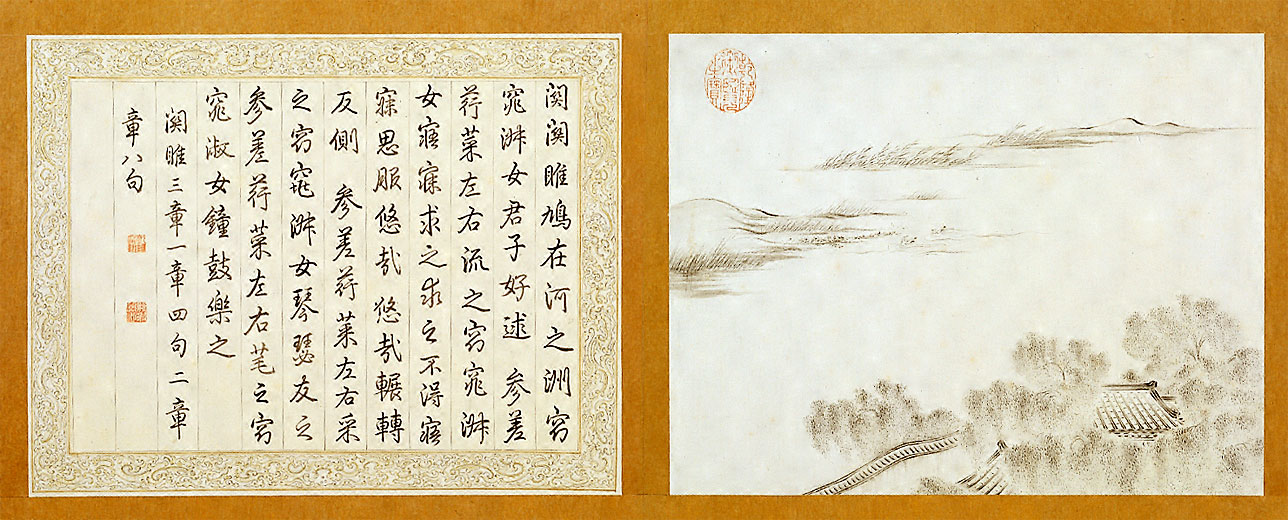

Literary Chinese was adopted in Korea, Japan, and Vietnam. The ''Oxford Handbook of Classical Chinese Literature'' argues that this adoption came mainly from diplomatic and cultural ties with China, while conquest, colonisation, and migration played smaller roles.Modern use

Classical Chinese was the main form used in Chinese literary works until the May Fourth Movement (1919), and was also used extensively in Japan, Korea, and Vietnam. Classical Chinese was used to write the Hunmin Jeongeum proclamation in which the modern Korean alphabet (

Classical Chinese was the main form used in Chinese literary works until the May Fourth Movement (1919), and was also used extensively in Japan, Korea, and Vietnam. Classical Chinese was used to write the Hunmin Jeongeum proclamation in which the modern Korean alphabet (hangul

The Korean alphabet, known as Hangul, . Hangul may also be written as following South Korea's standard Romanization. ( ) in South Korea and Chosŏn'gŭl in North Korea, is the modern official writing system for the Korean language. The ...

) was promulgated and the essay by Hu Shih in which he argued against using Classical Chinese and in favor of written vernacular Chinese. (The latter parallels the essay written by Dante in ''Latin'' in which he expounded the virtues of the vernacular ''Italian''.) Exceptions to the use of Classical Chinese were vernacular novels such as '' Dream of the Red Chamber''.

Most government documents in the Republic of China (Taiwan) were written in Classical Chinese until reforms in the 1970s, in a reform movement spearheaded by President Yen Chia-kan to shift the written style to vernacular Chinese. However, most of the laws of Taiwan are still written in a subset of Literary Chinese. As a result, it's necessary for today's Taiwanese lawyers to learn this language.

Today, pure Classical Chinese is occasionally used in formal or ceremonial occasions. The '' National Anthem of the Republic of China'' (), for example, is in Classical Chinese. Buddhist

Buddhism ( , ), also known as Buddha Dharma and Dharmavinaya (), is an Indian religion or philosophical tradition based on teachings attributed to the Buddha. It originated in northern India as a -movement in the 5th century BCE, and ...

texts, or sutra

''Sutra'' ( sa, सूत्र, translit=sūtra, translit-std=IAST, translation=string, thread)Monier Williams, ''Sanskrit English Dictionary'', Oxford University Press, Entry fo''sutra'' page 1241 in Indian literary traditions refers to an aph ...

s, are still preserved in Classical Chinese from the time they were composed or translated from Sanskrit sources. In practice there is a socially accepted continuum between vernacular Chinese and Classical Chinese. For example, most official notices and formal letters are written with a number of stock Classical Chinese expressions (e.g. salutation, closing). Personal letters, on the other hand, are mostly written in vernacular, but with some Classical phrases, depending on the subject matter, the writer's level of education, etc. With the exception of professional scholars and enthusiasts, most people today cannot write in full Classical Chinese with ease.

Most Chinese people with at least a middle school education are able to read basic Classical Chinese, because the ability to read (but not write) Classical Chinese is part of the Chinese middle school and high school curricula and is part of the college entrance examination. Classical Chinese is taught primarily by presenting a classical Chinese work and including a vernacular gloss that explains the meaning of phrases. Tests on classical Chinese usually ask the student to express the meaning of a paragraph in vernacular Chinese. They often take the form of comprehension questions.

The contemporary use of Classical Chinese in Japan

Japan ( ja, 日本, or , and formally , ''Nihonkoku'') is an island country in East Asia. It is situated in the northwest Pacific Ocean, and is bordered on the west by the Sea of Japan, while extending from the Sea of Okhotsk in the north ...

is mainly in the field of education and the study of literature. Learning the Japanese way ( kanbun) of decoding Classical Chinese is part of the high school curriculum in Japan. Japan is the only country that maintains the tradition of creating Classical Chinese poetry based on Tang dynasty's tone patterns.

The use of Classical Chinese in these regions is limited and is mainly in the field of Classical studies.

In addition, many works of literature

Literature is any collection of written work, but it is also used more narrowly for writings specifically considered to be an art form, especially prose fiction, drama, and poetry. In recent centuries, the definition has expanded to inclu ...

in Classical Chinese (such as Tang poetry) have been major cultural influences. However, even with knowledge of grammar and vocabulary, Classical Chinese can be difficult to understand by native speakers of modern Chinese, because of its heavy use of literary references and allusions as well as its extremely abbreviated style.

See also

*Classical Chinese grammar

Classical Chinese grammar is the grammar of Classical Chinese, a term that first and foremost refers to the written language of the classical period of Chinese literature, from the end of the Spring and Autumn period (early 5th century BC) to the ...

*Classical Chinese lexicon

Classical Chinese lexicon is the lexicon of Classical Chinese, a language register marked by a vocabulary that greatly differs from the lexicon of modern vernacular Chinese, or Baihua.

In terms of conciseness and compactness, Classical Chinese r ...

* Classical Chinese poetry

*Classical Chinese writers Classical Chinese writers were trained as compilers rather than as originators composing information. These writers in Classical Chinese were trained by memorizing extensive tracts in the classics and histories. Their method of constructing their ow ...

* Adoption of Chinese literary culture

* Kanbun

* Gugyeol

*Literary Chinese literature in Korea

Hanmunhak or Literary Chinese literature in Korea ( Hangul: 한문학 Hanja: 漢文學) is Korean literature written in Literary Chinese, which represents an early phase of Korean literature and influenced the literature written in the Korean la ...

* Literary Chinese in Vietnam

* Sino-Xenic vocabulary

** Sino-Japanese vocabulary

**Sino-Korean vocabulary

Sino-Korean vocabulary or Hanja-eo () refers to Korean words of Chinese origin. Sino-Korean vocabulary includes words borrowed directly from Chinese, as well as new Korean words created from Chinese characters, and words borrowed from Sino-Jap ...

** Sino-Vietnamese vocabulary

Notes

References

Citations

Sources

* * * * * * *External links

Classical Chinese for Everyone

Bryan Van Norden, 2004

Alex Amies, 2013

Chinese Texts: A Classical Chinese course

Mark Edward Lewis, 2014

Literary Chinese

Robert Eno, 2012-2013 (to access the book use provided PDF index file)

A Primer in Chinese Buddhist Writings

John Kieschnick, 2015

John Cikoski, 2011.

Microsoft Translator releases literary Chinese translation

(''Microsoft Translator Blog,'' August 25, 2021) {{Authority control Chinese language Chinese Korean language Japanese language Vietnamese writing systems